On this page

The Eromanga Basin is a Early Jurassic - Late Cretaceous basin.

The Eromanga Basin is a Early Jurassic - Late Cretaceous basin.

The Eromanga Basin encloses the multi-aquifer system of the Great Artesian Basin and overlies late Palaeozoic and older basins. It consists of a broad downwarp with two main depocentres — the Poolowanna Trough and the Cooper region.

See the Petroleum geology of South Australia. Volume 2: Eromanga Basin (Second edition) for information on Eromanga, Pedirka, Arckaringa and Simpson basin structural and tectonic history, new seismic mapping, litho- and biostratigraphy, source rocks and maturity, reservoirs, seals, trap development, discovered reserves, field reviews, undiscovered potential, exploration history, infrastructure, economics and land access considerations.

Eromanga Basin plays

Mackunda Formation play, Cooper Basin region

Coorikiana Sandstone play, Cooper Basin region

Summary

| Age | Early Jurassic - Late Cretaceous |

|---|---|

| Area in South Australia | 360 000 km2 (139 000 sq miles) |

| Exploration Well Density | 1 well per 128 km2 (1 well per 49 sq. miles) |

| Success ratio | 0.468 |

| Depth to target zone | 1200-3000m |

| Thickness | Up to 3000m |

| Hydrocarbon shows | Commercial discoveries of oil from almost every unit from the Poolowanna to the Coorikiana Sandstone in the Cooper region; oil recovery and shows in the Poolowanna Formation in the Poolowanna Trough region of the western Eromanga. |

| First commercial discovery | 1976 gas (Namur 1) 1978 oil (Strzelecki 3) |

| Identified reserves | Cooper region only, elsewhere - nil. |

| Undiscovered resources (50%) |

ERD estimate for Western Eromanga Basin, June 2006: 8.4 x 106 kL (52.8 mmbbl) total for Poolowanna, Hutton and Namur-Algebuckina |

| Production |

Cooper region only - refer to Production and statistics for a summary, or PEPS for more detailed information.

Elsewhere nil. |

| Basin type | Intracratonic |

| Depositional setting | Productive non-marine sequence overlain by non-productive marine, marginal marine, and non-marine sediments. |

| Reservoirs | Braided and meandering fluvial, shoreface and lacustrine turbidite sandstones. |

| Regional structure | Broad, four-way dip closed anticlinical trends in regional sag basin. |

| Seals | Lacustrine - floodplain shales and basin-wide volcanogenic sandstones. |

| Source rocks | Underlying Cooper Basin and siltstone; Birkhead and Murta formations' siltstone and coal. |

| Number of wells (July 2021) | 2807 (381 development/appraisal exclusively Eromanga targets) mostly in Cooper region |

Seismic line km | 105720 2D; 20290 3D km2 (135290 km) |

Prospectivity

The Eromanga Basin covers 1 000 000 km2 of central–eastern Australia, 360 000 km2 of which lies in South Australia. The Eromanga Basin encloses the multi-aquifer system of the Great Artesian Basin.

In South Australia, the Eromanga Basin overlies late Palaeozoic and older basins. It consists of a broad downwarp with two main depocentres — the Poolowanna Trough and the Cooper region — containing up to 3000 m of sediment. The central Eromanga Basin is overlain by the Tertiary to Recent Lake Eyre Basin. Eromanga Basin units crop out extensively on the western and southern margins.

Structurally, the Eromanga Basin is divided into two by the NE-trending Birdsville Track Ridge, a complex of related domes and ridges. The Poolowanna Trough in the NW contains a thick sand-dominated sequence in comparison to the Cooper region where intercalated shale and siltstone units occur.

Petroleum exploration commenced in the 1950s when licences covering the Cooper and Eromanga basins were first acquired by Santos, who went against conventional wisdom that commercial accumulations of oil would not be found in Mesozoic formations within the Great Artesian Basin.

Initial exploration involved surface mapping, stratigraphic drilling, aerial surveys, gravity and aeromagnetic surveys and seismic. The first petroleum well was drilled in 1959 and Cooper Basin gas was discovered in 1963.

The first commercial hydrocarbon to flow from the Eromanga Basin was gas produced from Namur 1 in 1976 (Cooper region). Oil was discovered in 1977 with an uneconomic flow from Poolowanna 1 in the Poolowanna Trough. The first economic oil flow was recorded from Strzelecki 3 (Cooper region) in the following year and this stimulated a major oil exploration program.

Since 1959 over 2000 wells have penetrated the Eromanga Basin sequence and over 100 000 km of seismic has been acquired. Exploration has concentrated in the Cooper region. A new phase of exploration for oil in the Eromanga Basin commenced in 2002 in the 27 new licences resulting from the expiry of PELs 5 and 6 in 1999. Most new entrant explorers are currently targeting Eromanga Basin oil plays.

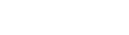

Eromanga Basin stratigraphy can be divided into three sequences — lower non-marine, marine and upper non-marine. Exploration effort is concentrated on the productive lower non-marine sequence. The Eromanga Basin unconformably overlies Permo-Triassic infrabasins, the Cambro-Ordovician Warburton, Amadeus and Officer basins and Proterozoic basement in South Australia.

In the Cooper region, the lower non-marine sequence consists of intertonguing braided fluvial sandstones (Hutton and Namur sandstones), lacustrine shoreface sandstone (McKinlay Member) and meandering fluvial, overbank and lacustrine sandstone, siltstone, shale and minor coal (Poolowanna, Birkhead and Murta formations).

In the Poolowanna Trough, the Poolowanna Formation (up to 130 m thick) is overlain by a thick sand-dominated unit (Algebuckina Sandstone). West of the northern Birdsville Track Ridge, Birkhead and Murta Formation shales pinch out into Algebuckina Sandstone. Algebuckina Sandstone crops out on the western and southern basin margin. Play analysis has been conducted by ERD for the Poolowanna Formation and Algebuckina Sandstone in the Poolowanna Trough region.

The non-marine sequence is succeeded conformably by a sequence reflecting transition from non-marine to marginal marine to open marine shale and sandstone. The basal unit, Cadna-owie Formation, is of significance for petroleum exploration as the top of the unit approximates a distinctive seismic reflector — the C horizon mappable over the entire basin. In 1998 DEM compiled a basin-wide C horizon data set from company seismic maps. Extending into Queensland, Northern Territory and New South Wales, as part of the National Geoscience Mapping Accord Cooper and Eromanga Basin project.

The upper non-marine sequence (Winton Formation) was rapidly deposited — up to 1100 m over ~8 million years. A period of erosion in the Late Cretaceous, caused by a switch in drainage from the Cooper region to the Ceduna Depocentre on the rifted southern margin, was followed by deposition of the non-marine Cainozoic Lake Eyre Basin.

A series of maps from the top of the Cadna-owie Formation to the base of the Eromanga Basin were compiled by DEM in 2020 as part of a groundwater model of the South Australian portion of the Great Artesian Basin (GAB).

See the DEM Maps and spatial data webpage and SARIG for further details of data and maps available for the Eromanga Basin.

Vertical migration of oil from Permian (Cooper Basin) source rocks has been widely accepted as the principal source of most Eromanga-reservoired oil (in the Cooper region). Both Cooper and Eromanga mature source rocks have contributed to oil accumulations in the region, however each oil accumulation needs to be considered on its merits with respect to the extent of mixing from Permian and Mesozoic sources. The Poolowanna and Birkhead formations contain organic-rich shales that are oil-prone and in places at peak maturity for oil generation, but volumetrically any oil generated from them is almost negligible in comparison with that from Permian source rocks. Lateral migration from these source areas has been proven on the Western Flank of the Cooper area in particular.

Phase separation is likely to have a major influence on the occurrence of liquid versus gas in the Cooper and Eromanga Basins (Hall et al, 2016). The fluids are a dew point system with primarily gas at depth. As hydrocarbons migrate into shallower reservoirs, the pressures reduce to below the saturation pressure and liquids separate out. Saturation pressure depends both on the gas to liquids ratio and the mutual miscibility of the two phases, which is in turn dependent on their composition.

Most oils in the Cooper area of the Eromanga Basin are now relatively dead with little or no gas. This is due to water washing in strong aquifer drive reservoirs, removing the light ends.

In the western Eromanga basin, the presence of thick Poolowanna, Birkhead and Murta formations is critical to evaluation of oil source potential. The marine sequence and upper non-marine sequence are immature for hydrocarbon generation over much of the basin. The underlying Simpson and Pedirka basins also contain mature source rocks and are well placed to charge Eromanga Basin reservoirs.

Principal reservoirs in the Cooper region are the braided fluvial Hutton and Namur sandstones (porosities up to 25%, permeability up to 2500 mD). Oil is also reservoired in meandering fluvial (Poolowanna and Birkhead formations), lacustrine shoreface (McKinlay Member), lacustrine turbidite (Murta Formation) and shallow marine (Coorikiana Sandstone) sandstones. Detailed petrophysical data is available from DEM for all of these Eromanga Basin reservoirs. A schematic section showing typical petroleum traps of the Eromanga Basin is shown in Eromanga Basin figure 6

In the Poolowanna Trough, principal reservoirs occur in the Poolowanna Formation (variable reservoir quality) and Algebuckina Sandstone.

In the Cooper region the structural framework of the Eromanga Basin is largely inherited from mild but widespread compression, regional tilt and erosion in the Late Triassic which produced the Nappamerri unconformity surface (N seismic horizon). Regional downwarping commenced in the Early Jurassic. Across the basin, Tertiary W–E compression reactivated Palaeozoic structures.

Seals consist of intraformational diagenetic sandstones, siltstones and shales of the Poolowanna, Birkhead and Murta formations in the Cooper region. In the Poolowanna Trough, they consist of intraformational siltstone and shale in the Poolowanna Formation and siltstone of the Cadna-owie Formation. Elsewhere in the basin, potential seals include the Cadna-owie Formation and Bulldog Shale – Wallumbilla Formation).

In the Cooper region, where the Nappamerri Group regional seal is thin or absent, oil and gas pools are found in coaxial Permian–Mesozoic structures (in some cases from the Patchawarra to Murta formations).

Trapping mechanisms within the Eromanga Basin are dominantly structural (anticlines with four-way dip closure or drapes over pre-existing highs) with a stratigraphic component (e.g. Hutton–Birkhead transition, Poolowanna, McKinlay Member and Murta Formation). The structure at the Coorikiana level is characterised by a desiccated fault pattern with no obvious preferred orientation and small irregular shaped fault blocks, with faulting predominately extensional in nature, providing for normal displacement.

Eromanga structures in South Australia are rarely filled to spill with oil — net oil columns are relatively thin compared to the height under closure, often due to poor sealing characteristics, but also due to late structural movements tilting closures.

Cooper Basin region of South Australia

Petroleum exploration in the Eromanga Basin in South Australia has traditionally concentrated in the portion underlain by the highly productive Cooper Basin, a relatively mature area. In addition, there is the likelihood that a significant amount of the oil found in this area has been sourced from the underlying Cooper Basin.

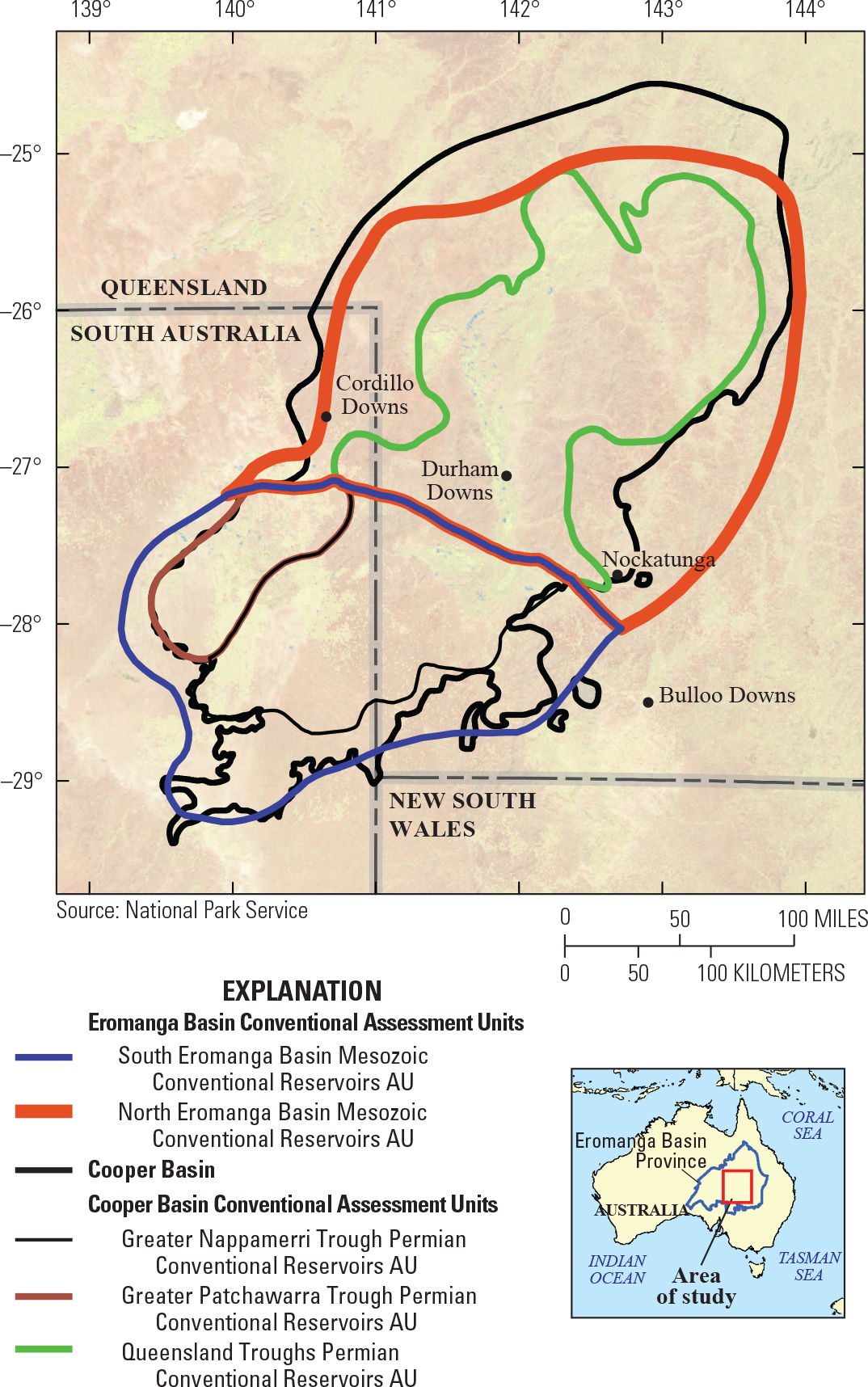

The USGS (Schenk et al 2016) estimated the undiscovered conventional oil and gas potential of the Eromanga Basin in South Australia and Queensland, as shown in their Figure 1 below. Table 1 summarises the results of this assessment. Further potential has also been assessed for the underlying Cooper Basin.

Figure 1. Map showing locations of five conventional assessment units in the Eromanga Basin Province, Australia (Schenk et al 2016)

Table 1 Undiscovered conventional oil and gas resources of the Cooper Basin region, Eromanga Basin (USGS, May 2016)

Note: MMBO = million barrels of oil or natural gas liquids. BCF = billion cubic feet. Results are fully risked estimates. F95 = 95% chance of at least the amount tabulated. Other fractiles are defined similarly.

Western Eromanga Basin

Areas to the west have had minimal exploration effort, with only one sub-economic discovery. Oil found here would probably be sourced from the Poolowanna and Birkhead formations or the underlying Pedirka and Simpson basins. Estimates of undiscovered resources in the western Eromanga are best carried out by a method that uses available geological data and Monte Carlo type statistical techniques to calculate, as a probability distribution, the undiscovered resources for each play.

For a commercial petroleum field to exist in the western Eromanga Basin, four essential components are required: a mature ‘source’, a ‘reservoir’ horizon, a ‘seal’ horizon and a structure over the reservoir horizon that will concentrate the petroleum in economic quantities and that was present at the time of the petroleum expulsion from the source rock. Usually this is an anticline, but stratigraphic traps can also be important. When all four of these occur together, a petroleum ‘play’ or a potential target for exploration exists.

Maps for each play, taking into account distribution of source, seal and reservoir were constructed. Figure 7 summarise these for the Poolowanna Formation, Hutton Sandstone and Namur–Algebuckina sandstones plays respectively.

Table 2 summarises the results of the assessment of the undiscovered resources of the western Eromanga Basin at various probability levels (Morton and Hill, 2007).

Table 2: Undiscovered recoverable oil resources of the western Eromanga Basin

UNDISCOVERED POTENTIAL 106 kL (mmbbl) | ||||||

| PLAY | Probability that the ultimate potential will exceed the stated value: | |||||

| 90% | 50% | 10% | ||||

| Poolowanna | 0.3 | (1.3) | 0.6 | (3.8) | 1.9 | (12.0) |

| Hutton | 0.6 | (3.8) | 2.4 | (15.1) | 7.6 | (47.8) |

| Namur-Algebuckina | 1.0 | (6.3) | 4.1 | (25.8) | 13.0 | (81.8) |

| Total | 3.5 | (22.0) | 8.4 | (52.8) | 18.6 | (117.0) |

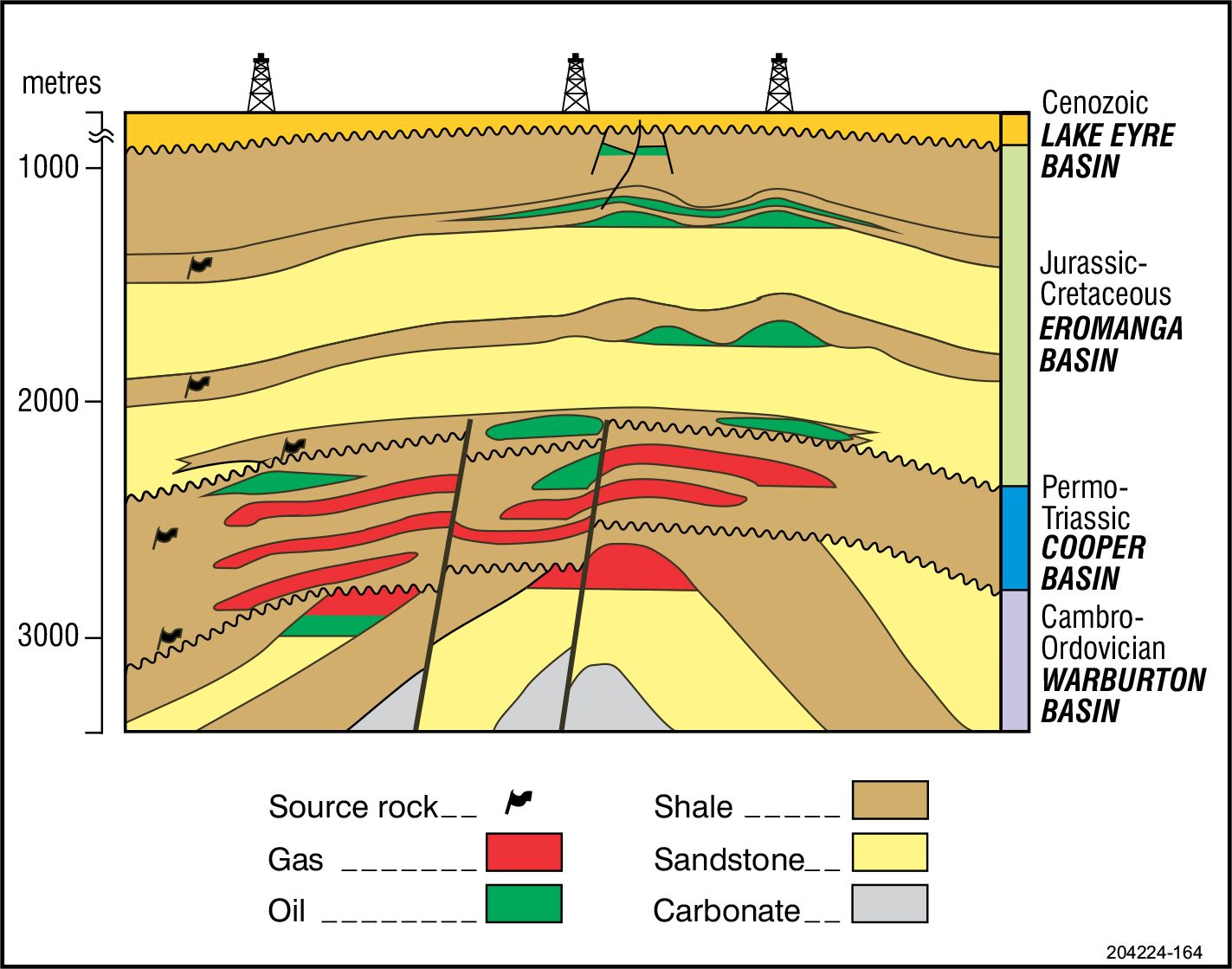

Several National Parks and Wildlife reserves overlie the Eromanga Basin Reserve Land. (South Australia Reserved Land figure).

Exploration is permitted in the Munga-Thirri–Simpson Desert Regional Reserve, the Innamincka Regional Reserve, the Witjira National Park, Tallaringa Conservation Park and the Kati Thanda–Lake Eyre National Park. Exploration is not permitted in the Malkumba–Coongie Lakes National Park, the Munga-Thirri–Simpson Desert Conservation Park or the No-Go Special Management Zone of the Innamincka Regional Reserve.

The initial 2001 right to negotiate (RTN) agreements in the Cooper Basin for the CO-98 PEL application areas were groundbreaking in Australia as the first conjunctive agreements (covering exploration and production) that provide certainty in enabling any explorer, the Aboriginal parties, and the state being able to benefit from any commercial discoveries made.

The state has also commenced the RTN process for additional PELs in the Eromanga and Arrowie basins and it is likely that existing RTN agreements will continue to form a practical precedent. Any agreements will provide for protection of the heritage and cultural interests of the Aboriginal parties.

Compulsory relinquishment of roughly 36% (19 150 km2) of the areas in current Cooper region PELs will precede competitive bidding from 2009. In anticipation of the calling for work program bids in 2009, negotiations opened in 2006 to develop a conjunctive Indigenous land access agreement (ILUA) for the regions already covered with land access agreements resulting from earlier RTN proceedings. These negotiations involve the Aboriginal Legal Rights Movement, the three native title parties already familiar with the RTN process, the South Australian Government, and petroleum exploration and production company representatives (through the South Australian Chamber of Mines and Energy).

The draft framework agreement established in 2006 will be the subject of necessary formal negotiations as required by the Native Title Act 1993, with a hope to formalise ILUAs for the whole of the Cooper Basin region in 2007.

The first conjunctive ILUA in Australia in a proven petroleum province was concluded in February 2007 with the Yandruwandha–Yawarrawarrka native title claimants over a major portion of the South Australian Cooper Basin. This will provide greater certainty and expedite the grant of PELs in a way that remains fair to native title claimants and sustainable in relation to exploration and production investment. The application of conjunctive ILUAs will enable land access more quickly and with lower transaction costs than serial RTN proceedings. The successful implementation of conjunctive ILUAs for Cooper Basin petroleum exploration and production will serve as a model for analogous agreements elsewhere in the state.

Negotiations in respect to formalising conjunctive petroleum ILUAs with the remaining two native title claimant parties in the Cooper Basin are progressing.

In summary, conjunctive ILUAs are proposed as an evolutionary, additional, alternative to the RTN process already working comparatively well in South Australia. Indeed, conjunctive ILUAs will be an attractive incentive to achieve competitive bids, with explorers knowing the terms of land access prior to lodging bids.

A number of applications are being held over the western part of the Eromanga Basin pending resolution of native title issues.

Figure 8 shows the licence status at the time of publication. Use this link for further information on holders of petroleum tenements in South Australia.

Altmann MJ and Gordon HM, 2004. Oil on the Patchawarra Flank - some implications from the Sellicks and Christies oil discoveries. In: Boult, P.J., Johns, D.R. and Lang, S.C. (Eds), PESA’s Eastern Australasian Basin Symposium II, Adelaide 2004. Petroleum Exploration Society of Australia. Special Publication, pp. 29-34.

Bradshaw, B.E., Rollet, N., Iwanec, J., Bernecker, T. 2022. A regional chronostratigraphic framework for play-based resource assessments in the Eromanga Basin. The APPEA Journal 62 S392-S399.

Boult PJ, Lanzilli E, Michaelsen BH, McKirdy DM and Ryan MJ, 1998. New model for the Hutton/Birkhead reservoir seal couplet and the associated Birkhead-Hutton(!) petroleum system. APPEA Journal, 38(1):724-744.

Cotton TB, Scardigno MF and Hibburt JE eds, 2006. The petroleum geology of South Australia. Vol. 2: Eromanga Basin. 2nd edn. South Australia. Department of Primary Industries and Resources. Petroleum Geology of South Australia Series.

Gravestock DI, Moore PS and Pitt GM eds, 1986. Contributions to the geology and hydrocarbon potential of the Eromanga Basin. Geological Society of Australia. Special Publication, 12.

Hannaford, C., Young, M., Watts, C., Charles, A., Cooling, J. & Rollet, N. 2022. Palynological data review of selected wells and new sampling results in the Great Artesian Basin. Data package and supplementary detailed reports. Record 2022/01. Geoscience Australia, Canberra.

Kalinowski, A., Tenthorey, E., Seyyedi, M., Clennell, M.B. 2022 The search for new oil and CO2 storage resources: residual oil zones in Australia. The APPEA Journal 62(1) 281-293.

Kramer L, McKirdy DM, Arouri KR, Schwark L and Leythaeuser D, 2004. Constraints on the hydrocarbon charge history of sandstone reservoirs in the Strzelecki Field, Eromanga Basin, South Australia. In: Boult PJ, Johns DR and Lang SC eds, PESA’s Eastern Australasian Basin Symposium II, Adelaide 2004. Petroleum Exploration Society of Australia. Special Publication, pp. 589-602.

McKirdy DM, Arouri KR and Kramer L, 2005. Conditions and effects of hydrocarbon fluid flow in the subsurface of the Cooper and Eromanga Basins. University of Adelaide report on ARC SPIRT Project C39943025 for PIRSA and Santos Ltd. South Australia. Department of Primary Industries and Resources. Report Book, 2005/00002.

Nakanishi T and Lang SC, 2002. Constructing a portfolio of stratigraphic traps in fluvial–lacustrine successions, Cooper–Eromanga Basin. APPEA Journal, 42(1):65-82.

Norton, C.J. & Rollet, N. 2022. Regional stratigraphic correlation transects across the Great Artesian Basin - Eromanga and Surat basins focus study. Record 2022/02. Geoscience Australia, Canberra.

O’Neil BJ Ed, 1989. The Cooper and Eromanga Basins, Australia. Proceedings of the Cooper and Eromanga Basins Conference, Adelaide, 1989. Petroleum Exploration Society of Australia, Society of Petroleum Engineers, Australian Society of Exploration Geophysicists (SA Branches).

Rollet, N., Vizy, J., Norton, C., Hannaford, C., McPherson, A., Tan, K.P., Ransley, T. & Kilgour, P. 2022. Geological and hydrogeological architecture of the Great Artesian Basin ‒ A framework for developing hydrogeological conceptualisations. Record 2022/xx. Geoscience Australia, Canberra. (unpublished)

Sales, M., Altmann, M., Buick, G., Dowling, C. Bourne, J., Bennett, A. 2015 Subtle oil fields along the Western Flank of the Cooper/Eromanga petroleum system Extended Abstract APPEA 2015.

Vizy, J. & Rollet, N. 2022 . Great Artesian Basin geological and hydrogeological surfaces update. Record 2022/xx. Geoscience Australia, Canberra. (unpublished)